In Iran, I had a friend whose uncle was a film director who would smuggle in DVDs of foreign movies. She’d borrow these DVDs from him and share them with me. Later, I became acquainted with a locksmith, who had a narrow store next to a coffee shop that I frequented. In addition to making copies of keys, he had lists of films by Bergman, Tarkovsky, Antonioni, Godard, and Ozo, among other directors, on his walls. Besides keys, he would copy any of the movies on the lists that you wanted (there was no copyright enforcement in Iran). Later, when I first arrived in Toronto, my wife and I visited Toronto International Film Festival’s Cinematheque during cold winter nights, an experience that comforted us during those early days of homesickness.

I have often been told that my writing includes visual and cinematic elements, and I attribute the imagery in my work, in part, to my intimate relationship with film. With the recent publication of my novel South, I revisited some of the movies that have influenced the novel’s creation.

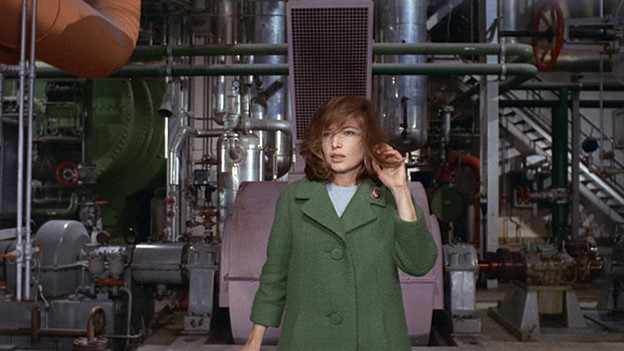

Red Desert by Michelangelo Antonioni

This 1964 movie by Antonioni is probably one of my all-time favourites. The movie follows Giuliana (Monica Vitti) who lives with her son and her husband in the industrial northern part of Italy after an auto accident caused her significant emotional distress. Giuliana’s husband, Ugo, who manages a petrochemical plant, does not fully understand the source of Giuliana’s mental state. There is also Corrado, Ugo’s friend, who is there to recruit workers for an industrial operation in Patagonia, Argentina. Giuliana confides in Corrado and becomes romantically involved with him, but ultimately finds herself in a recurring isolated state.

Alienation and a critique of industrialization are obvious themes of Red Desert, but the movie also generates a sense of mystery through its strange and arresting cinematography. It reminds me of what Becket said of Joyce’s writing that it “is not about something; it is that something itself.” The film is more mood-focused than plot-based. Vitti’s amazing performance; the imagery of the petrochemical plants, with each shot looking like a painting; and the interesting use of colour—Antonioni had the crew paint over the trees to establish the exact colours he wanted—are essential aspects of the film. While the setting is in northern Italy, the giant machinery conveys a sense of the uncanny as if we are in a dystopian landscape; the isolation and alienation are intensified by the presence of the solitary figures against the imposing machinery.

For South, I was inspired by how the setting plays a major role in portraying the protagonist’s emotional state, by the imagery of machinery and the poetic rendition of industry, as well as by the movie’s minimal reliance on exposition and backstory.

Red Desert, Michelangelo Antonioni, 1964

Alphaville by Jean Luc Godard

This 1965 French New Wave movie by Godard mixes elements of a detective story with science fiction. Lenny Caution is a secret agent posing as a journalist who enters Alphaville (a technocratic dystopia controlled by a dictatorial computer named Alpha 60) from the outlands. His initial mission is to find the missing agent Henri Dickson and assassinate Professor von Braun, the architect of the Alphaville state. Alphaville is a society where the logic of the computer has taken over: anyone showing feelings is executed by being shot in a swimming pool where people watch and clap and female dancers retrieve the body. Dictionaries are being continuously updated to remove any words that evoke emotions.

The movie is shot in black and white and is filmed at night in Paris without any typical science fiction props. There is a disorienting feel right from the start as Lenny arrives at his hotel in Alphaville. Things seem slightly off, starting with the female hotel attendant (later introduced as a seductress) showing Lenny to his room. There is an awkward conversation and then she is suddenly undressing to get into the bath with him as we hear shots. Lenny is abruptly defending himself against his unknown enemies.

I was intrigued by the movie’s use of genre elements (both sci-fi and noir), the stylish decor, and the threat and unpredictability of Alphaville’s world that was heightened by the claustrophobic feeling of the interiors, the sudden movements of the camera, and the voice-over narration.

In one of the scenes, Lenny is asked by the computer, “What transforms darkness into light?” “Poetry,” he replies. A critique of science enthusiasts and a testament to the power of words, language, and love, this prophetic movie feels even more apt in the age of social media and big data.

Alphaville, Jean Luc Godard, 1965

Solaris by Andrei Tarkovsky

This 1972 movie is based on the science-fiction novel of the same title by Stanislaw Lam. Psychologist Kris Kelvin travels to the space station orbiting the planet Solaris to investigate the emotional state of the scientists on the station and what has gone wrong in their mission. What he discovers—experiences himself—is mysterious hallucinations linked to his past and his lost wife, Hari. With this movie, Tarkovsky was trying to move beyond the limits of the science-fiction genre. He used some of the paintings by old masters (Bruegel and Rembrandt) as inspiration for his set designs, which is an interesting choice for a movie about a space station. He said that he was neither interested in showing the material details of the future nor including any technologically exotic elements. “I'm interested in problems I can extract from fantasy. Man and his problems, his world, his anxieties. Ordinary life is also full of the fantastic. Life itself is a fantastic phenomenon.”

The claustrophobic feeling of the spaceship, the sense of looming mystery, Tarkovsky’s approach to genre, as well as Solaris becoming a place for the representation of the past—all of these elements from the film shaped my writing of South.

Solaris, Andrei Tarkovsky, 1972

Zama by Lucrecia Martel

Based on a book of the same title by Antonio Di Benedetto, this 2017 movie by Lucrecia Martel is a Kafkaesque tale of an 18th century Spanish magistrate Don Diego de Zama (Daniel Giménez Cacho) who is assigned to a remote location in Argentina (today’s Paraguay) and his descent into madness. Zama is initially expecting to be reassigned to Lerma, where his wife and children are located and waiting for him. While there are rumors of a vicious bandit named Vicuña Porto going around, Zama keeps himself occupied by spying on indigenous women and trying to seduce a Spanish noblewoman without success. Disappointed by his lack of reassignment, Zama finally joins a small army to capture and kill Vicuña Porto. Things turn even more surreal and strange from here: the colors become more vivid, the narrative twists and goes sideways instead of moving forward, and the unnatural high-pitched sounds of the jungle dominate the soundscape.

A sensory fever dream, Zama is an in-depth representation of alienation and colonial despair. Martel says of the novel by Di Benedetto: “What we call masterpieces of literature manage to weave a very particular toxin into their letters, one that sickens, maddens and then transforms humans into better animals. It’s not something you can explain by describing events or characters. It’s something that happens in the writing. In the order and selection of the words…” As a fan of the novel, I was really taken by the surreal imagery, minimal use of exposition, the sound design, and Martel’s methods for transforming the source text into an equally powerful, original work of art.

Zama, Lucrecia Martel, 2017

Babak Lakghomi is the author of Floating Notes. His fiction has appeared in American Short Fiction, NOON, Ninth Letter, New York Tyrant, and Green Mountains Review, and has been translated into Italian and Farsi. Babak was born in Tehran, Iran, and currently lives and writes in Toronto. Learn more here.